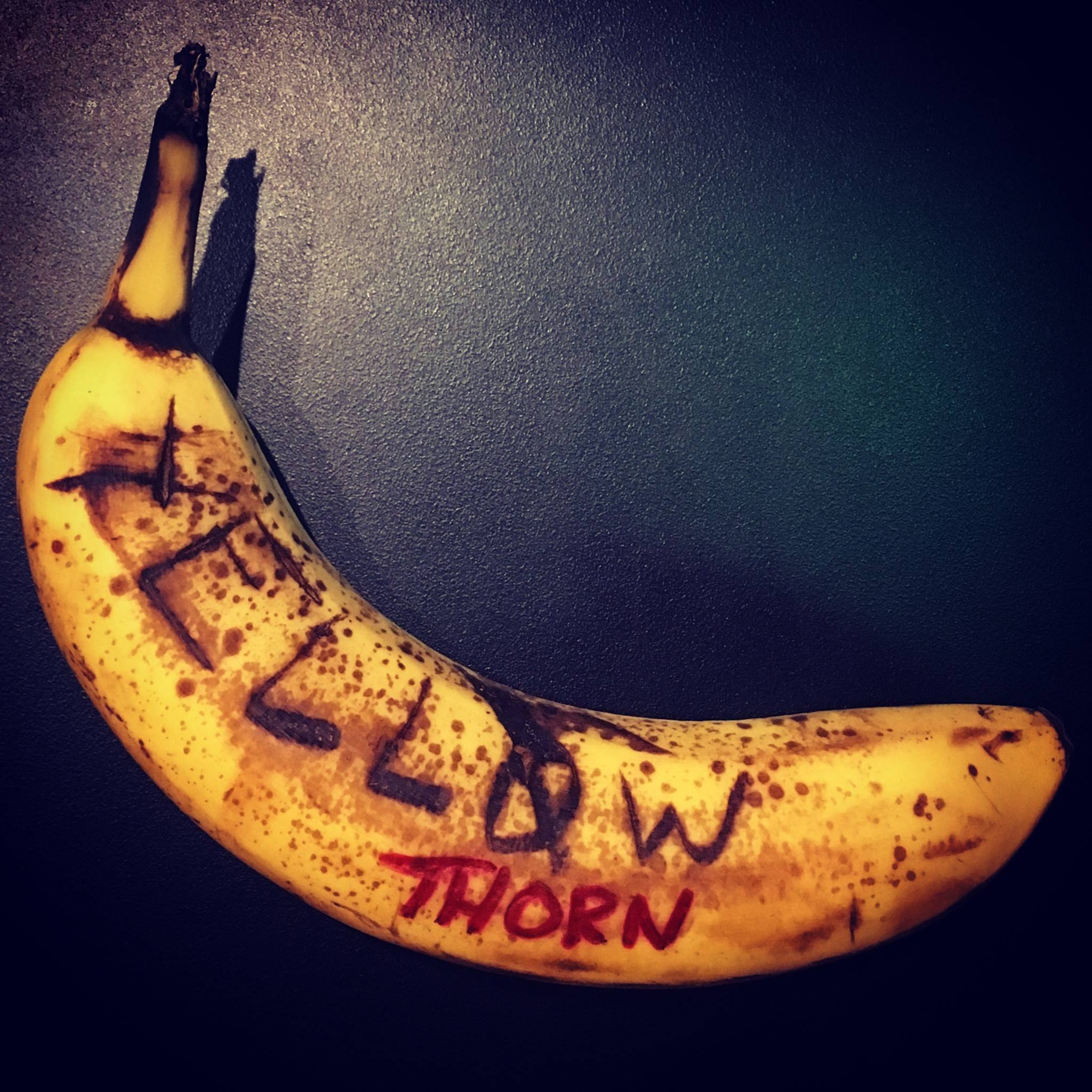

Roan Yellowthorn

Hey guys, Katie here, and I’m back after a relaxing few weeks at a resort. (That is a lie. I spent the last few weeks building the courses I’m teaching this semester. I am making an active choice to lie to both you and myself about that.) I’m so excited you got to hear from James and Zoe— sometimes our little Festival Family feels like a unit because we’re basically a music-loving transformer. We each have strengths and fill in gaps, but man, move the spotlight, and it’s crazy what each person on the team can do. We’re all so excited about the musicians we’ve already announced that every week is like unwrapping a present, and this week, it’s my turn.

When it comes to Roan Yellowthorn, the present is wrapped really, really well. Comprised of singer/songwriter/pianist Jackie McLean and multi-instrumentalist/producer Shawn Strack, Roan Yellowthorn is a perfect ethereal pop act: brilliant, playful lyrics; creative, sparse production; and music that, like liquid, would fill whichever glass you poured it in. McLean’s vocals are strong but not taut: there’s a bounce-back effect, especially on songs like “Lie,” where she has written something clever and interesting, but still sings it straightly and plaintively:

Sometimes you lie

You lie about where you go…

I need you to lie

But don’t lie through your mouth

Don’t lie through your teeth

Just lie down right here with me

It’ll be OK

We can lie all day you see

That kind of lyin’ don’t bother me

The wordplay and creativity reflects McLean’s literary background (says the pleased creative writing professor) and shows her to be someone who is careful— both in terms of the way we usually use that word and as in “full of care.” Every note, every word in her songs is considered and measured. That’s part of why Strack’s Lorde-esque production, where each instrument or melody is built carefully to put the spotlight on the stark beauty in the vocals and the creativity in the lyrics, is so effective.

When I first started listening to Indigo, I was excited before I even hit “play.” I love intro/outro records, because the first thing I know when I pick it up is that the artist was deliberate not only in the track list order, but in the music itself. This winter, I’ve revisited Remy Zero’s The Golden Hum, partially to try and trick my brain into thinking the sun is out. I always listen to the record straight through, though: the intro preps you for the rest of the record. The right intro throws a colored lighting gel over the spotlight of the rest of the record. It’s like taking one last deep breath before going over the side of a boat. The intro on Indigo, is similarly perfect— and even though I immediately knew it, I couldn’t figure out why on first listen. McLean brilliant at sleight of hand, both lyrically and musically, but there’s a dissonance to the intro. It’s dark and winding, with a child’s voice singing “Row Your Boat” while McLean vocalizes underneath a haunted sound, like early Sarah McLachlan. And then when it breaks into her first single, “Talk About It”— well, it’s almost confusing. Her voice is so effortlessly lovely: strong and even. It might have been four or five listens in before I got exactly how the intro was functioning, though.

The haunted intro is necessary: these lyrics, against the brightly colored palette of the music, are the ghosts themselves. She needed to telegraph that though these songs are catchy and fun, they also have depth and layers— which she literally creates by layering a one-minute start. I’ve come to think of Indigo as a boat: at least, I feel that way about the songs between the intro and outro. But the beginning and end are a fade-in from your real life into the world of the music, and the outro allows you passage back to the real world. For a moment, you’re deep in the ocean.

Songs like “Mark My Words” translate our normal feelings into more poetic and lyrical language: “You’re going to miss me with the anger burns out/ You’re going to think to yourself, ‘What did I do’?” McLean’s voice seems filtered through an old radio, like we’re all sitting around a porch or living room speaker, listening to torch songs. But some of these songs feel urgently contemporary: also a breakup song, “Fingerless Gloves” focuses on one image and uses it to build the world of the whole relationship.

Hey, I was just wondering how you are

If you like your new place so far

If you’re happy with what you’ve got

If you think about me a lot

If everything turned out the way you thought

And hey

What did you say

To her about me

When you saw me on the street

Did you tell her who I was

That I gave you those fingerless gloves

That one time, long ago

I knew things she didn’t know

That we were once in love

Did you tell her who I was?

Did you tell her who I was?

This is painful for so many reasons: there’s a Harvey Danger song, “Little Round Mirrors,” where singer Sean Nelson says of a falling star, “It’s hardly worth even a footnote in your memoir,” and it seems like that’s what the narrator is afraid of: being the footnote. If that. The metaphor of fingerless gloves— something that is an accessory but not as comforting as real gloves, not as warm— works perfectly. But I think McLean has built an even more complicated world than that with the metaphor: fingerless gloves are something that many people love or wear— but you wouldn’t get them for a casual partner. You have to really know the person you’re giving them to, and that seems to be the point of the whole song. Our narrator knows this man, and she isn’t sure she trusts the new woman, even though she doesn’t get a vote. Is she protective or jealous? It could go either way, but the voice is captivating. Plus— as good as those first few lines are— that’s not even the best writing in the song.

Hey, I was just wondering if we could talk….

Then I turned into myself

Then I turned into myself

Then I turned into somebody else

Then I turned into myself

Usually I would say that any kind of repeating line, especially a simple one like that, wasn’t much to write home about— but the variation on the line, the fact that she’s herself, herself, someone else— and then she had to come back to herself to be the person we’re introduced to as our narrator. That’s an incredibly strong image but it’s also something women have been talking about and dealing with in lyrics for decades and decades: Carly Simon’s “You say we’ll fly like two birds through the night/ But soon you’ll cage me on your shelf/ I’ll never learn to be just me first, by myself;” Tori Amos’s “So I turned myself inside out in hopes someone would see;” or even Carole King’s generally thought to be beautiful love song, “Where You Lead,” where she says, “I always wanted a real home with flowers on the window sill/ But if you want to live in New York City, baby, you know I will.” McLean’s voice adds a beautiful chapter— and let me be clear, not a footnote— to the litany of women who are looking for their identity both in and outside of their relationship. The narrator in this song is conflicted, but that doesn’t mean she’s weak. In fact, none of the characters on this record are.

I can’t emphasize how important it is to listen to the record straight through— because the darkness in the intro is reflected in the outro as the lyrics become more questioning and self-doubting. Mirroring Aimee Mann’s brilliant “Long Shot,” instead of launching the grenade at the partner who has wronged her, the narrator in McLean’s song is willing to examine her own role, no matter how sad or angry it makes her: “Did I fuck it up? Did I do something wrong?/ If it doesn’t work out, is it all my fault?” As the song travels through rivers of doubt, regret, and confusion, it settles on one thing that seems both a comfort and a dissociation with the world:

On the outside

Coz I never felt like I belonged

On the outside

Where I can do no wrong

On the outside

I’ll be a goddess among men

On the outside

I’ll never feel alone again

When I’m on the outside

I’ll never come back down again

But remember what I said about McLean’s literature background: read those lyrics straight through, and then take “on the outside” off the beginning— “I never felt like I belonged on the outside/ Where I can do no wrong/ On the outside”— that’s a drastic cry from being condemned to the outside. The song functions both ways, and actually, underscores the duplicity that runs through Indigo’s heart: the songs are upbeat and catchy, but inherently intellectual; McLean’s voice is clear and strong, but has soft edge; Strack’s production is both minimalist and clean, but not so much so that it feels overworked; and perhaps most important, in every single song, the narrator is looking in from outside and being looked at by characters on the outside. She imagines conversations where people examine her and their relationships with her, but then she also looks at herself under the same microscope. Roan Yellowthorn, as a band, is an outsider: but you won’t be able to tell that on a casual listen. This is a record you need to listen to in a quiet room, no phone in hand, and ready to move words around, listen for double meanings, and appreciate the quiet beauty in perfect simplicity.

Welcome to the family, Roan Yellowthorn!

Roan Yellowthorn’s Web home

And on the Faced Book

And the ‘Gramm

Plus the TubeYou

And don’t forget the Twitters